Monica Piccinini

9 May 2023

Similar to our current political & economic systems, the food system is no longer serving us; mainly driven by power, profit and greed, resulting in global food insecurity and impacting directly on our health and the environment.

We’ve seen a sharp increase in food insecurity worldwide, driven not only by climate change and multiple conflicts, but also by an unbalanced food system fuelled by corporate power.

As the world population is projected to reach 9.8 billion in the next 27 years, there’s an urgent need to address issues related to our food system, or we may be facing a worldwide famine sooner than expected. We’ve already seen signs of this in many parts of the world.

“The right to food is the right to have regular, permanent and unrestricted access—either directly or by means of financial purchases— to quantitatively and qualitatively adequate and sufficient food corresponding to the cultural traditions of the people to which the consumer belongs, and which ensure a physical and mental, individual and collective, fulfilling and dignified life free of fear”, according to the United Nations.

Corporate Power

Giant agribusiness corporations hold the power and control over our food systems, with the ability to influence governments and decision-makers, through lobbying, with the direct intention of shaping policies in many ways.

Their objectives and tactics are questionable, with the tendency to favour their own interests, focusing on profits and maximising shareholder value, rather than addressing hunger and malnutrition.

According to ‘Who’s Tipping the Scales’, a report published by IPES Food, the international panel of experts on sustainable food systems:

“A bold, structural vision to counter the corporate takeover of food-related global governance – one that support central roles for people, governments, and democratic, public-interest-based decision-making, is urgently needed.”

It’s clear that the voices of the most vulnerable communities across the world, and mostly affected by hunger and environmental impact caused by this industry, must be heard.

These giant and dominant agribusiness corporations influence the global organisations we most trust, which should be there to defend our interests. To the surprise of many, agribusiness associations were sitting directly at the UN governance table at the 2021 UNFSS, UN Food Systems Summit.

One must also question the kind of relationship between the private sector and international governance bodies and institutions about potential conflicts of interest.

According to the IPES Food report, in 2020, a private philanthropic foundation, The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, was the second largest donor to the CGIAR, the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research.

Another partnership that raises some eyebrows is the FAO’s, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, partnership with CropLife International, CLI, an agrochemical lobby organisation, whose members include Syngenta, BASF, FMC and Bayer (acquired Monsanto in 2018).

PAN North America, Pesticide Action Network, mentioned that instead of putting the profit of CropLife International members before farmers and consumers worldwide, the FAO must invest in solutions, including agroecology and take stronger action on ending the usage of highly hazardous pesticides, HHPs.

We’ve also seen increase in consolidation, a large number of mergers and acquisitions, allowing these corporations to dominate the agribusiness sector. This allows these giants to have a profound influence on governance and the structure of our food system, resulting in anti-competitive market practices.

Our Health & the Environment

These corporations have significant funding at their disposal to influence policies and regulations, such as pesticides, biosafety, patents, intellectual property, as well as trade and investment agreements.

Bayer AG spent over USD 9 million lobbying the US government in 2019, after it acquired Monsanto. At the time, they were reviewing the re-registration of one of the company’s main products, glyphosate (Roundup), which is considered a toxic herbicide. In the US, Bayer has been contesting billion of dollars in settlement claims to end lawsuits over accusations that glyphosate causes cancer.

They are also responsible for shaping science by sponsoring academic research favouring their corporate interests, influencing governance and policies. This was seen in the agrochemical and processed food sectors.

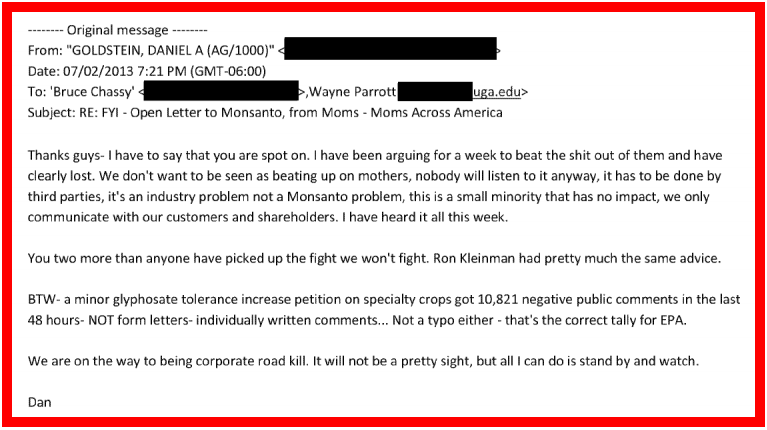

As proof of this, below is an internal email between Monsanto executives obtained by lawyers representing plaintiffs in the Roundup® litigation, where they suggest ‘beating the s**t out of’ a mother’s group expressing concern over the effects of GMOs and Roundup® on their children.

Monsanto also tried to influence science by sponsoring various ghostwriting academic articles questioning scientific studies that raised concern over its product’s safety, glyphosate.

Another very concerning issue related to the health of our children is the fact that this industry continuously lobbies against mandatory public health measures, including taxes on ultra-processed foods, UPF, sugary drinks and front of package labeling, as well as restrictions on marketing of unhealthy foods to our children. This has a gigantic impact on their health and also creates pressure on our health systems.

A reported example of this was when a children’s cereal manufacturer attempted to sue Mexico after the country tried to amend a food packaging regulation called NOM-5, in order to protect their children from the marketing of unhealthy foods. The regulation established that certain unhealthy products would be prohibited from putting children’s animations and characters on their packages.

The invention of novel foods also raises some red flags. On March, The Defender, a publication defending children’s health, published a piece on Bill Gates’ latest invention, an edible food coating called Apeel, which is an odourless, colourless and tasteless coating for vegetables and fruit, which potentially extends the life span of these products, keeping it fresher for up to two times longer.

Apeel has already received the green light from US regulators, but some questions still remain unanswered surrounding the safety of the product, as the company is relying mainly on existing scientific studies, as no new science has been required to evaluate and test the product.

We seem to be completely exposed and reliant on these corporations to carry out their own safety studies, without the scrutiny of independent regulators and scientific studies.

According to the 2011 UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, companies are expected to develop their own internal procedures to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for how they address their impacts on human and environmental rights in global supply chains.

It’s clear that the way we grow our food has a massive impact not only on our physical and mental health, but also on our environment, affecting fauna and flora, the health of our soil, water and air.

Recently, we have seen a sharp increase of fungal disease in crops, affecting 168 crops listed as important in human nutrition, according to FAO of the United Nations. Despite spraying fungicides, farmers are losing between 10-23% of their crops to fungal disease every year, including rice, corn, soybeans and potatoes.

According to a study published at Nature journal, this issue is mainly because of the adaptability of fungi to meet modern agricultural practices. Monocultures entail vast areas of genetically uniform crops, an ideal ground for fast-evolving organisms, such as fungi. Another problem is the increasingly widespread use of antifungal treatments, leading to fungicide resistance.

The use of pesticides and toxic chemicals are increasing exponentially across the world, causing havoc to our health, the soil, polluting water sources, the air, animals and plants.

Industrial agriculture, including cattle farming, soybean, palm oil, sugar cane, corn, wheat, GMOs, monoculture production, is responsible for the deforestation of rainforests, the Cerrado, and many other parts of the world, causing destruction and degradation.

In Brazil, 2.8% of landowners own over 56% of all arable land, and 50% of smallholder farms have access to only 2.5% of the land. Overall, the land is in the hands of a small number of industrial farms.

We must rethink the way we grow our food and we all have the right to access nutritious and healthy food and decide what we eat.

Digital Farming

The agribusiness sector spends vast amounts on research and development, making it extremely hard for smaller companies to compete with them, capitalising on patent protection and intellectual property rights.

Why? Because they can!

Patent protection and intellectual property is another issue that should be catching everyone’s attention.

Giant tech companies, such as Amazon and Microsoft, among others, entered the food sector focusing on power, control and profit. Small farmers and local food systems are struggling, as they can’t afford to use this high tech data gathering technology. They are also located in remote areas where these types of services can’t reach.

We can see an increasing movement of powerful integration and control between the companies that are supplying products to farmers, such as tractors, drones, pesticides, etc., and the tech giants. They feed and control farmers with information, and at the same time have direct access to consumers.

The aim is to integrate millions of farmers into a wide centrally controlled network by encouraging and forcing them to buy their products. This digital infrastructure is run by platforms developed by tech companies that run cloud services.

Fujitsu farm workers, located just outside Hanoi, carry smartphones supplied by the company, which monitors their every single movements, productivity, the amount of hours they work, etc., all stored on the company’s cloud. This is extremely worrying, as this practice could easily lead to labour exploitation.

Similar to Fujitsu, other companies investing heavily on this type of digital farming platforms include Microsoft’s Azure FarmBeats, Bayer’s Fieldview, BASF’s Xarvio, Syngenta’s CropWise, Yara’s Yaralrix and Olam’s OFIS, Olam Farmer Information System.

It’s essential to point out the extent of data gathering these platforms are capable of, including real time data and analysis on the farmers soil condition and water, crops growth, pests and diseases monitoring, weather, humidity, climate change, tractor monitoring, etc.

Some of these corporations are also trying to eliminate the “middlemen” by selling directly to consumers, which may be attractive proposition to many, if the idea is mainly to help farmers and small vendors directly, but somehow they may use digital platforms to increase their pricing power over farmers.

An important question we must ask these companies, regulators and our governments: who controls all this data, what do they do with it and who gives the advice?

The influence a few powerful corporations have in food governance must be scrutinised. Governments should be leading in the field of food security and not leaving it in the hands of those that put profit over longevity of life. It may seem a drastic change to the world as we know it, but it may be the only way to bring back a balance in the global food system and secure our quality of life and ultimately our survival.